Tropical Marine Ecology Field Course in Abu Dabbab, Egypt

Resource partitioning is a fundamental ecological mechanism driving biodiversity. It encapsulates the idea that different species, usually closely related or belonging to the same guild, tend to exploit different resources to minimise interspecific competition and thus enhance coexistence.

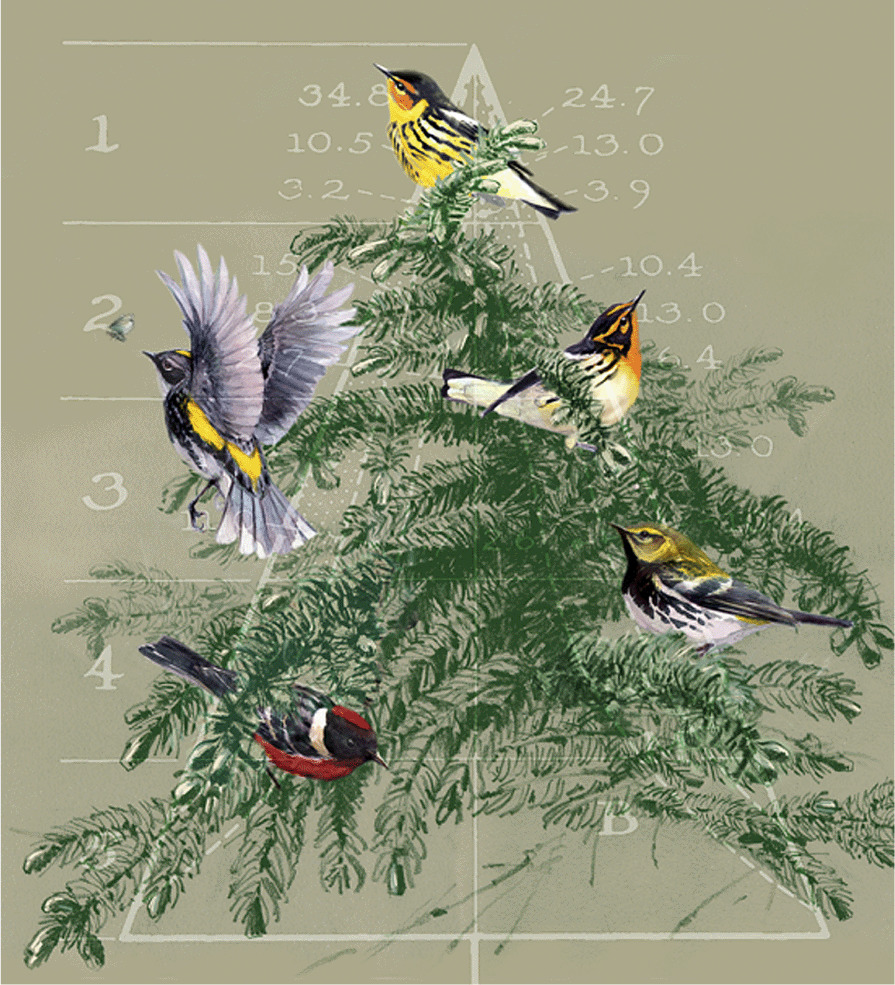

The concept was originally studied in detail by Robert MacArthur in 1958 is his seminal work on warblers of the genus Dendroica (now Setophaga) in coniferous forests of the Northeastern USA. In his study, MacArthur described how 5 congeneric species from the genus Setophaga, of similar sizes and shapes and all mainly insectivorous, could coexist in the same habitat. As in turns out, the Cape May (S. tigrina), Myrtle (S. coronata), Black-throated green (S. virens), Blackburnian (S. fusca) and Bay-breasted (S. castanea) warblers are able to live together because they forage in different parts of the conifers in the temperate forests where they reside, thus potentially accessing different prey species.

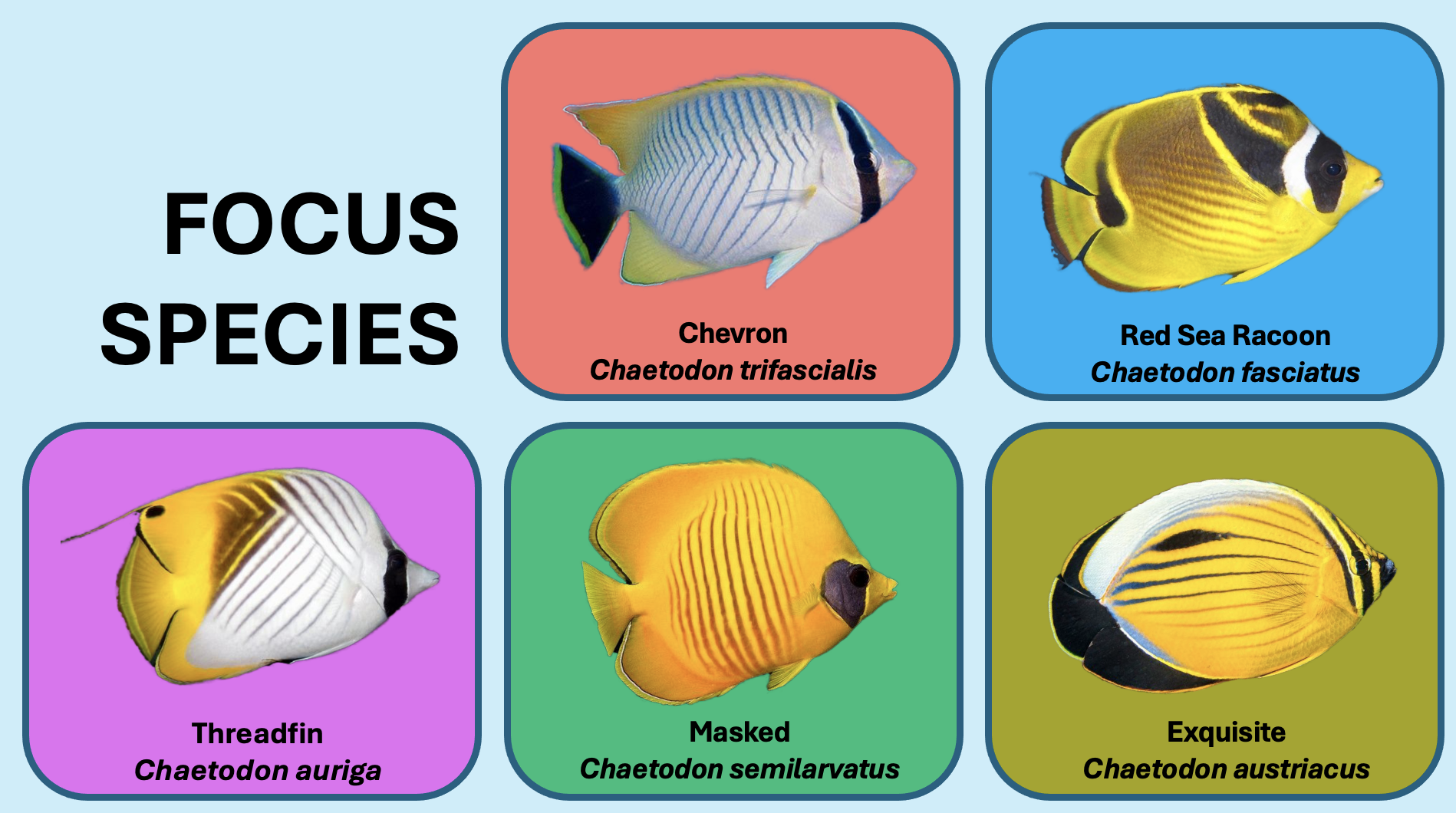

Last week, during the Tropical Marine Ecology field course in the Red Sea, I had the pleasure to help a group of keen marine biology students revisit this hypothesis in a marine system. Team Albatross, formed by Will, Alex, Neo, Leanne, Jenny, Rafe, Hannah and Rosie (from left to right in the picture) set out to study resource partitioning across 5 species of butterflyfish of the genus Chaetodon.

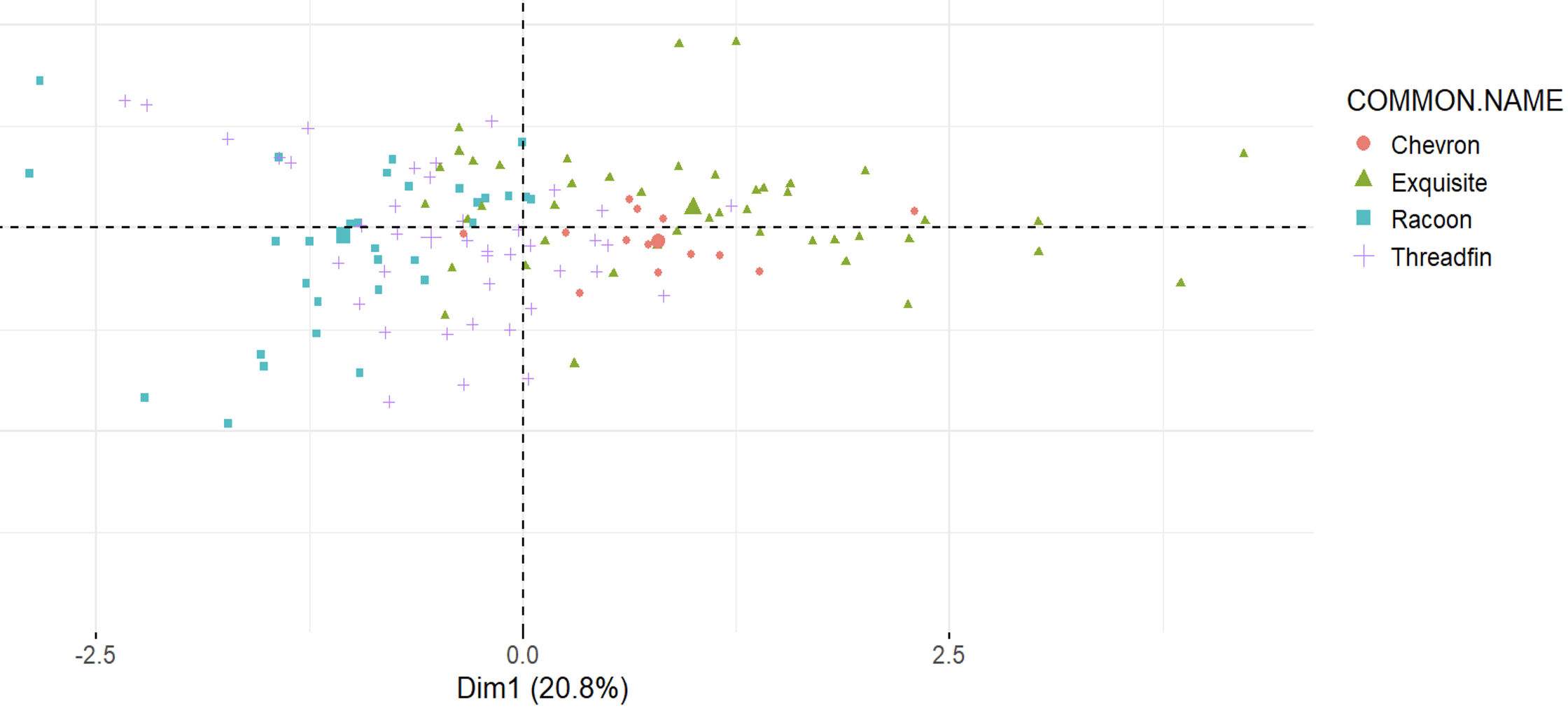

After days of intense field work, observing the behaviour of many fish across the reef of Abu Dabbab, the team was able to show resource partitioning in this genus of fish. The Threadfin (C. auriga), Chevron (C. trifascialis), Red Sea Racoon (C. fasciatus), Masked (C. semilarvatus) and Exquisite (C. austriacus) butterflyfish split their foraging efforts not only across different prey items including several species of corals, jellyfish and algae, but they also forage at different heights in the reef and at day and night.

Overall a very interesting project, loads of fun and adventure, and why not… also a little bit of thinking!