Dr Ricardo Martínez-García visits the lab

This week, my good friend and colleague, Dr Ricardo Martínez-García, from the Centre for Advanced Systems Understanding in Germany, visits the lab!

He will be working with me on the theoretical modelling of territoriality-driven dispersal and will be around for interesting discussions!

About Ricardo:

Ricardo got his PhD in Physics from the Institute for Cross Disciplinary Physics and Complex Systems (IFISC, Spain) in 2014. After that completed a postdoctoral training at the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Princeton University (USA) until 2019. Between 2019 and 2022 he was an Assistant Professor at the South American Institute for Fundamental Research and the Institute for Theoretical Physics of the State University of São Paulo (Brazil). Since December 2022 he is a Young Investigator Group Leader at the Center for Advanced Systems Understanding (CASUS; Görlitz, Germany) where he leads the Dynamics of Complex Living Systems research group.

His research seeks to understand and quantify how individuals behave in response to various interactions between them and with the environment, and how these behaviors drive community and ecosystem-level processes. Among those, he is particularly interested in emergent spatiotemporal patterns and their ecological and evolutionary implications. To answer these questions, he studies a variety of systems at various scales, from microbial communities to entire landscapes. For each of these, he develops mathematical models in which population-level processes result naturally from a detailed description of individual-level interactions and use them to investigate (eco)-system level processes that occur at the ecological and/or evolutionary scale. When possible, we test model predictions with experimental and field data. This approach ultimately allows us to use emergent population-level patterns as a bridge between individual behaviors and ecological and evolutionary scales.

He will present a couple of seminar at the Biosciences and the Maths Departments to share his research with us!

Bioscience: To leave or not to leave: a mechanistic model for the decision-making process behind ungulate partial migration

ABSTRACT

Despite the importance of ungulate migrations, we lack a complete understanding of why some ungulates species migrate and some do not. Moreover, at the population level, some migrate and others remain behind as residents, a phenomenon known as partial migration. Even though progress has been made towards understanding long-term fitness benefits of partial migration, the underlying decision-making process that makes some individuals migrate and others remain within one single range remain unknown. In this presentation I will combine empirical data from three different migrant ungulate species and mathematical modeling to address this question. I will first show that, across these three ungulate species, the number of residents is unrelated to total population size, a pattern predicted by no previous modeling framework. Next, I will introduce a new model of ungulate partial migration wherein individuals probabilistically decide to start migrating based on the intensity of environmental and social cues. Within this modeling framework, residents arise for most parameter combinations and the number of residents is largely invariant with total population size. Therefore, this new model explains the ubiquity of residents in migratory ungulate populations and presents novel patterns to be tested with further data collection.

Maths: Population dynamics models with non-local spatial interactions: from spatial patterns to species coexistence

ABSTRACT

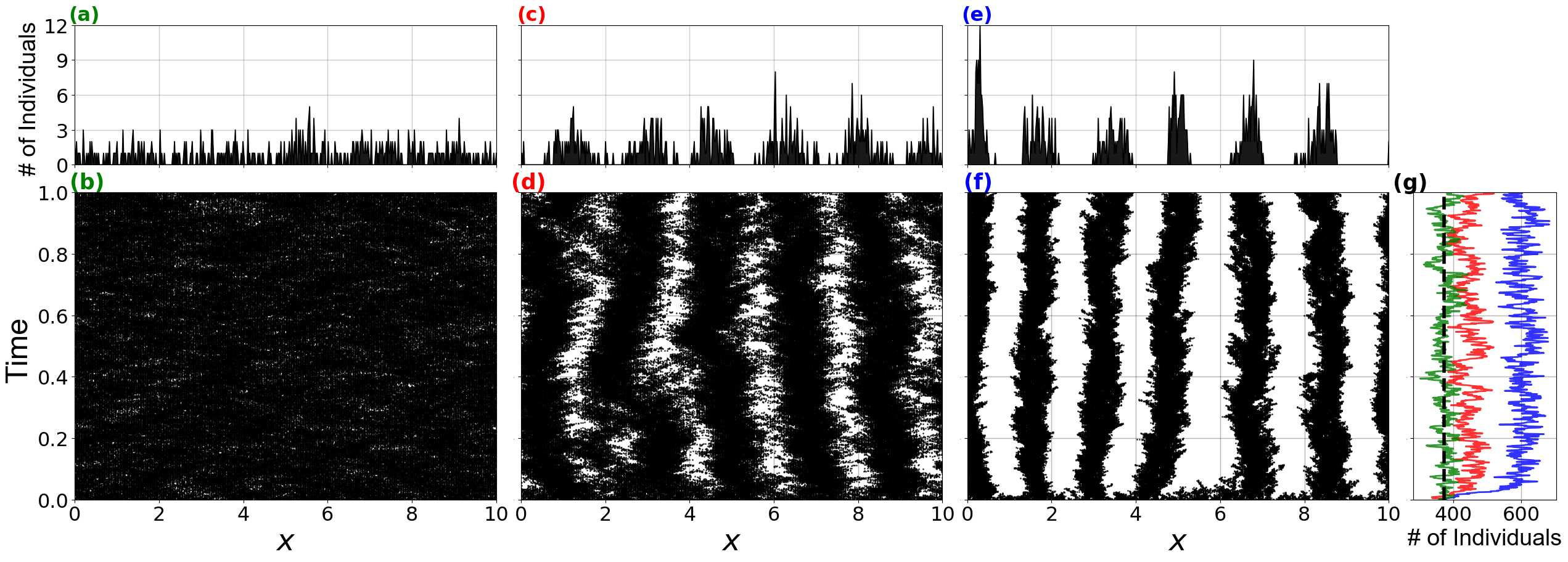

From microbial colonies to entire landscapes, biological systems often self-organize into regular spatial patterns, which might have significant ecological consequences. Several models have been proposed to explain the emergence of these patterns. Most of them rely on a Turing-like activation-inhibition scale-dependent feedback whereby interactions favoring growth dominate at short distances and inhibitory, competitive interactions dominate in the long-range. However, the importance of short-range positive interactions for pattern formation remains disputable. Alternative theories predict their emergence from long-range inhibition alone. In this presentation, I will explain how self-organized patterns might emerge in purely competitive models. I will first present in which conditions long-range competition alone can generate regular patterns of population density in systems with one and two species. Then, I will discuss the ecological implications of those patterns both for population persistence and species coexistence.